Researchers from the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore (NUS Medicine), have made a groundbreaking discovery regarding asymptomatic carriers of a multidrug-resistant strain of Escherichia coli sequence type 131 (E. coli ST131). These carriers can harbor large amounts of the bacterium in their gut for extended periods without showing any symptoms, consequently unknowingly passing it on to their household members.

Published in Nature Communications, this study is believed to be the first in Asia to investigate how this antibiotic-resistant bacterium spreads within communities. E. coli is a common type of bacteria found in the intestines of humans and animals. While most strains are harmless and even beneficial for gut health, certain strains can cause diseases when they acquire specific genes that make them pathogenic.

E. coli ST131 is a globally widespread and antibiotic-resistant strain that primarily causes urinary tract infections but can lead to more severe conditions like kidney infections and sepsis. Antibiotic resistance, a growing concern in both healthcare settings and communities, is fueled by bacteria like E. coli ST131, known as “superbugs.”

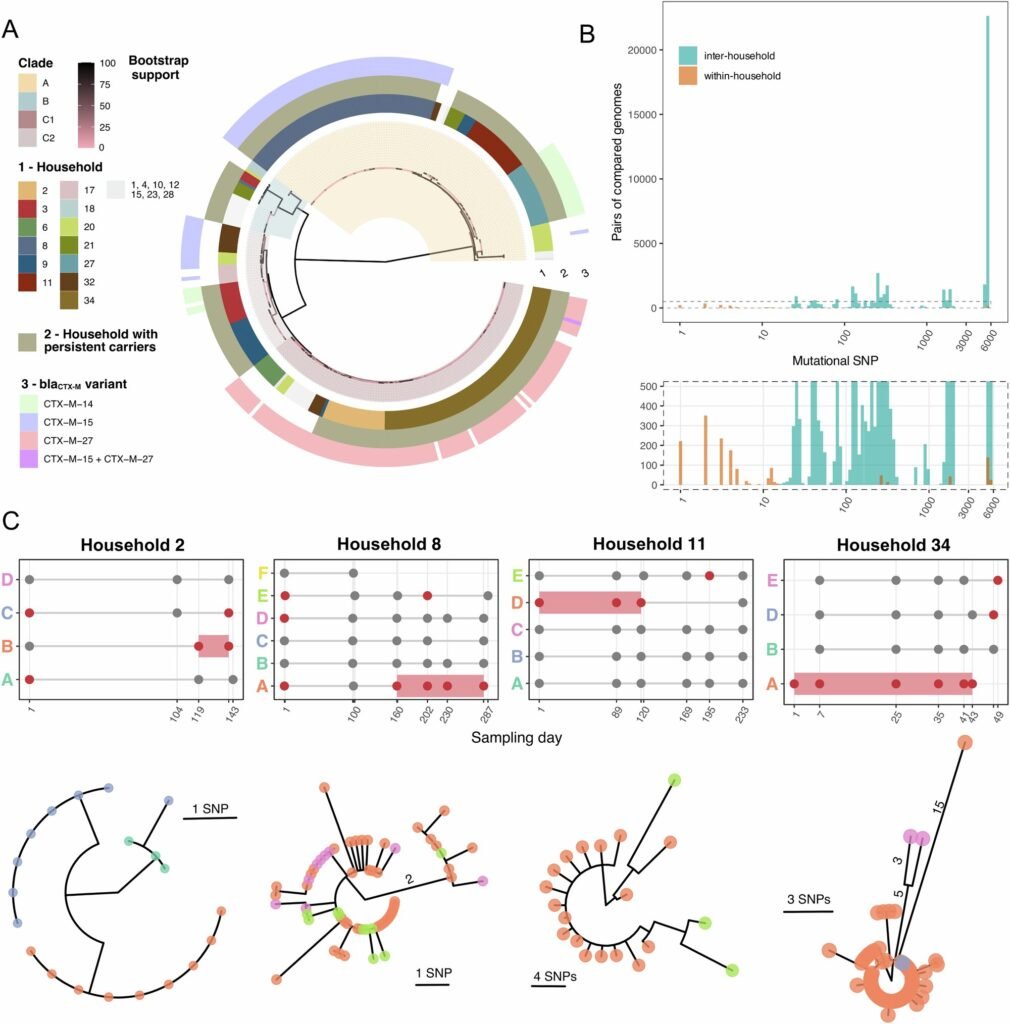

The research team followed 34 families in Singapore, collecting stool samples from 135 participants to trace the spread of E. coli ST131 within households. They discovered that a small number of individuals carried the bacterium persistently and in high amounts over long periods, acting as silent carriers. These carriers were likely the source of transmission to their family members, who carried similar bacterial strains. This highlights the role of asymptomatic carriers in sustaining the spread of resistant bacteria in communities.

Dr. Mo Yin, leading the study, emphasized the importance of identifying individuals carrying high levels of resistant bacteria without symptoms to implement targeted prevention strategies. Good personal hygiene practices at home and developing new methods to reduce long-term carriage of resistant bacteria are crucial.

Potential strategies include vaccines, probiotics, prebiotics, or fecal transplants, but further research is needed to determine their effectiveness. Professor Paul Tambyah stressed the need for community-based solutions to contain antibiotic resistance before it leads to challenging-to-treat infections.

Future studies will delve into the gut microbiome of participants to understand how the balance between beneficial and harmful bacteria influences the long-term carriage of resistant strains. These findings will contribute to global efforts to combat the rise of antibiotic resistance.

In conclusion, this research sheds light on the silent spread of resistant bacteria within households and underscores the importance of targeted prevention strategies and good hygiene practices to curb antibiotic resistance in communities. The study serves as a crucial step towards developing practical solutions to contain the spread of superbugs like E. coli ST131.