The debate surrounding the future of life expectancy continues to intrigue scientists as they analyze trends and data to make predictions. Over the course of the 20th century, life expectancy experienced a remarkable surge, with individuals born in 1900 living to an average age of 62 and those born in 1938 living to around 80.

A recent study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences delved into the question of whether individuals born between 1939 and 2000 would see similar increases in life expectancy. Researchers from institutions such as the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (MPIDR) and the University of Wisconsin-Madison examined data from 23 high-income and low-mortality countries to forecast future trends.

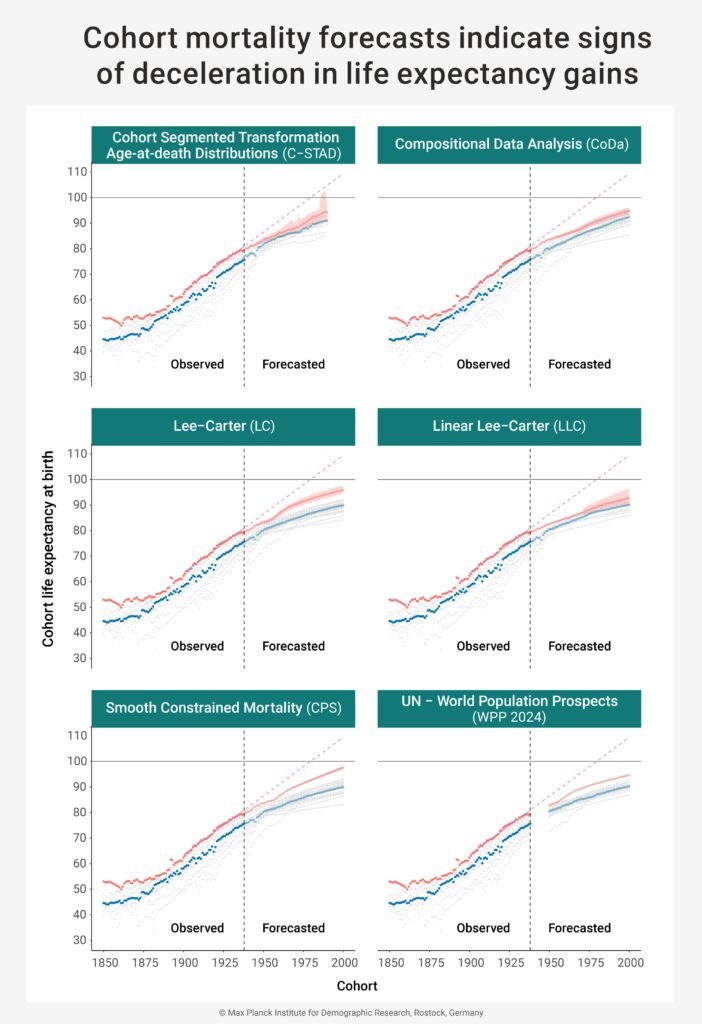

The analysis revealed a slowdown in the rate of life expectancy gains for current generations compared to the rapid progress seen in the early 20th century. Various mortality forecasting methods were employed to predict how life expectancy would evolve, taking into account factors such as past trends and current mortality rates.

The study’s findings indicated that individuals born in 1980 are unlikely to reach the age of 100 on average, a stark contrast to the rapid advancements in life expectancy witnessed in previous generations. The researchers attribute this deceleration to the fact that past increases in longevity were largely driven by improvements in survival rates among infants and young children, which have already reached optimal levels.

While forecasts are valuable tools for planning and policymaking, they come with inherent uncertainties. External factors such as pandemics, medical breakthroughs, and societal changes can greatly influence actual life expectancy outcomes. As such, it is crucial for governments, healthcare systems, and individuals to adapt to changing trends and recalibrate their expectations for the future.

The implications of slower life expectancy gains extend beyond individual planning to broader societal considerations. Governments must adjust healthcare policies, pension schemes, and social programs to accommodate shifting demographics. Likewise, individuals may need to rethink their retirement savings, long-term planning, and expectations for their golden years.

In conclusion, while the future of life expectancy may not follow predictable trajectories, ongoing research and data analysis provide valuable insights for shaping policies and personal decisions. By staying informed and flexible in our approach, we can better navigate the complexities of a changing demographic landscape.