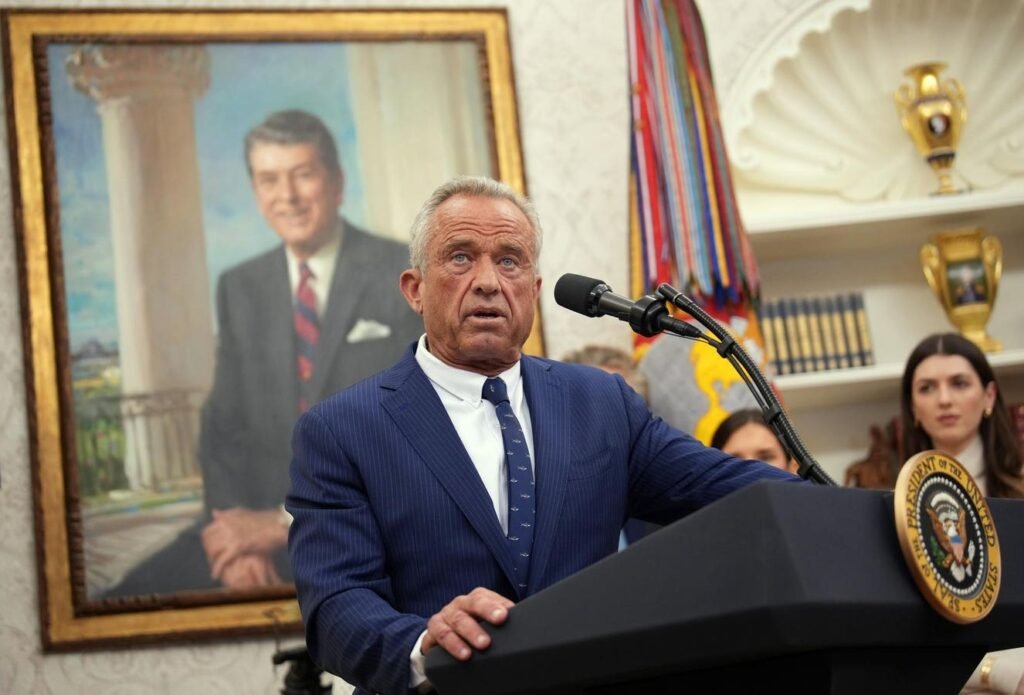

WASHINGTON, DC – FEBRUARY 13: Robert F. Kennedy Jr. speaks after being sworn in as Secretary of … More

Chronic disease prevention is a noble goal. And it’s one the secretary of Health and Human Services, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., has talked about a lot as part of his Make America Healthy Again campaign. But HHS is gutting or deprioritizing some of the nation’s most successful efforts at prevention, from smoking and HIV prevention to promotion of vaccinations.

The department is preparing to release new dietary guidelines by the end of this year, presumably ones aimed at lowering obesity rates, which in turn could in the long run reduce the prevalence of certain chronic diseases. Yet pushing for behavioral change of the kind Kennedy wants to have happen on a large scale isn’t new. It’s proven to be a slow process and difficult to accomplish. By contrast, many of the prevention programs the administration has cut or eliminated altogether have demonstrated success and are considerably easier to implement.

After the second death of a child from measles during the current outbreak that began in West Texas, Kennedy endorsed vaccination to prevent measles. But he stopped short of explicitly recommending that parents get their children vaccinated. And he praised alternative measles treatments of two vaccine-skeptic doctors after attending the funeral of an unvaccinated, previously healthy 8-year-old girl who died from virus.

Kennedy’s track record points to vacillating between backing standard childhood vaccinations and making statements or overseeing cuts in funding that threaten to undermine this public health tool. An article in U.S. News & World Report chronicles the inconsistencies in policy direction. Perhaps most notably, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention buried a measles forecast report that emphasized the need for vaccinations while the agency intends to fund a large study to examine the debunked theory linking autism to vaccines.

The deep budget cuts at HHS have also hampered the nation’s disease-detection capacity and pandemic preparedness with respect to pathogens such as bird flu, according to experts. And eliminating agencies’ entire communications teams has impeded the ability to effectively disseminate information to the public.

Kennedy argues that the federal government’s bureaucracy is bloated and that HHS needs to operate more efficiently. Nevertheless, the types of cuts as well as their scope don’t seem to be aligned with MAHA goals.

Cuts to smoking prevention and cessation programs, for example, don’t square with the aim of decreasing rates of chronic disease. Smoking is a leading cause of deaths and multiple chronic diseases, including cancer and cardiovascular conditions. Furthermore, shutting down government offices devoted to HIV prevention as well as other sexually transmitted diseases isn’t consistent with MAHA.

The list of conditions for which HHS programs have been gutted is long and far-ranging. It even includes stopping work focused on preventing birth defects, injuries and gun violence and shuttering the Office of Long Covid Research and Practice, among other things.

And the CDC’s Division of Population Health was practically eliminated in the mass layoffs. The division’s focus was promoting health and preventing chronic diseases, as MedPage Today explains.

MAHA’s Long-Term Goal Of Changing America’s Diet

There’s a litany of HHS budget decisions that could undermine efforts at disease prevention. But how about Kennedy’s long-term goal of changing America’s diet? Well, even here, budgetary cuts may hinder progress. Moreover, while Kennedy says his department is making important changes to the nation’s dietary guidelines, which could help to curb obesity rates, these aren’t coming until the end of this year.

The United States dietary guidelines get updated every five years and are intended to provide evidence-based advice on what to eat and drink for optimal health. They also partly determine what’s included in national food assistance programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition and Assistance Program (formerly known as food stamps) as well as public school lunches.

Kennedy told National Public Radio two months ago that President Trump expects him to show “measurable impacts on a diminishment of chronic disease within two years.” Presumably this would include obesity. Roughly 40% of adult Americans are obese. Rates have been steadily rising since 1980. The U.S. has experienced a small dip in recent years, possibly linked to the use of popular GLP-1 weight loss drugs. But these medicines are not high on the list of priorities for HHS to address the problem, as evidenced by the decision this month not to have Medicare or Medicaid pay for them.

Kennedy wants to tackle the issue through lifestyle modification, including dietary and other behavioral changes. Integral to his vision are plans to “fix” the food system. This includes improving food safety and eliminating additives or “harmful chemicals.” The Food and Drug Administration exercises oversight in this area, as it regulates roughly four-fifths of the U.S. food supply. But recent cuts to FDA staff that performs safety regulations belie Kennedy’s promises.

And if altering dietary habits to diminish chronic disease needs to be accomplished in less than two years, as Trump apparently expects, that may be a tall order. Positive results as a consequence of behavioral change are possible, but usually only after long periods of time. Consider, for example, a recent finding that increased physical activity was associated with reduced all-cause mortality in more than 2 million individuals with an 11–year follow-up. Similarly, a meta analysis tabulating the results of more than 150 studies examining the impact of dietary changes had a median follow-up of almost five years.

Besides the issue of timing, it must be noted that much of what Kennedy says about diet and exercise is not new and has been tried before by Democratic administrations. Former first lady Michelle Obama led a program called “Let’s Move,” which was aimed at curbing childhood obesity.

President Barack Obama announced the first lady’s role in leading a national public awareness effort to improve the health of children with dietary and exercise guidance. “To meet our goal,” he said, “we must accelerate implementation of successful strategies that will prevent and combat obesity. Such strategies include updating child nutrition policies in a way that addresses the best available scientific information, ensuring access to healthy, affordable food in schools and communities, as well as increasing physical activity.”

Twelve years later, the Biden administration convened the second White House Conference on Hunger, Nutrition and Health in 2022, 50 years after the first was held. The administration soon began implementing a new national strategy for “ending hunger and increasing healthy eating and physical activity so fewer Americans experience diet-related diseases.” The approach included the