A recent study conducted at the University of Michigan sheds light on how cells manage molecular crises, offering valuable insights into cellular responses to stress. Led by Stephanie Moon, Ph.D., an assistant professor of Human Genetics at U-M Medical School, the research focused on the mechanisms cells employ to prevent RNA traffic jams under stress conditions.

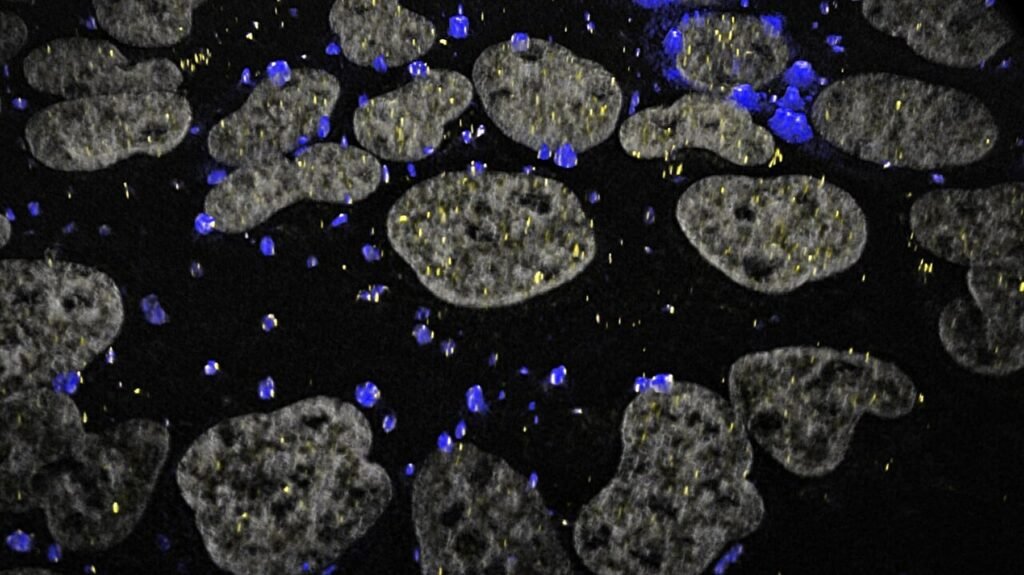

In healthy cells, most RNA molecules are covered with ribosomes, which act as miniature factories translating genetic instructions into essential proteins. When cells face stressors like heat, toxins, or inflammation, most cellular processes, including protein production, are temporarily halted to enhance cell survival. During this response, ribosomes detach from RNAs, leading to the formation of stress granules where unprotected RNAs accumulate until normal conditions are restored.

However, certain messenger RNAs (mRNAs) need to be expressed during stress to aid in cell recovery and adaptation. These specialized mRNAs play a crucial role in responding to cellular crises, akin to emergency vehicles rushing to an accident scene on a highway. Understanding how these mRNAs avoid entrapment in stress granules is essential for cell function and survival.

The study, detailed in a paper published in the journal Genes & Development and spearheaded by Ph.D. candidate Noah Helton, revealed that vital mRNAs evade stress granules by interacting with ribosomes. Trapping these mRNAs in stress granules would impede protein production when cells require it the most. Disruptions in stress granule dynamics are linked to various diseases, including ALS, cancer, and other conditions characterized by heightened or chronic stress.

The research team delved into the role of uORFs (upstream open reading frames), special sequences at the 5′ untranslated region of certain mRNAs, in promoting ribosome recruitment. Their findings showed that the presence of uORFs facilitated ribosome association with mRNAs under stress, preventing their sequestration into stress granules. Surprisingly, even a single ribosome on an mRNA was sufficient to shield it from condensing into a granule, contrary to previous beliefs requiring multiple ribosomes for this purpose.

The study’s fundamental insights could pave the way for new therapeutic interventions targeting diseases where the stress response is dysregulated. By elucidating how specific mRNAs evade stress granules, the research opens avenues for maintaining healthy protein synthesis in various pathological conditions.

As the team continues to explore the interplay between uORFs and mRNAs, their discoveries hold promise for advancing treatment strategies and enhancing our understanding of cellular responses to stress. Such research endeavors contribute to the development of innovative therapies aimed at restoring normal cellular functions in disease states.

For more information, the study titled “Ribosome association inhibits stress-induced gene mRNA localization to stress granules” can be accessed in the journal Genes & Development. This research was conducted at the University of Michigan, underscoring the institution’s commitment to groundbreaking scientific inquiry and medical advancements.