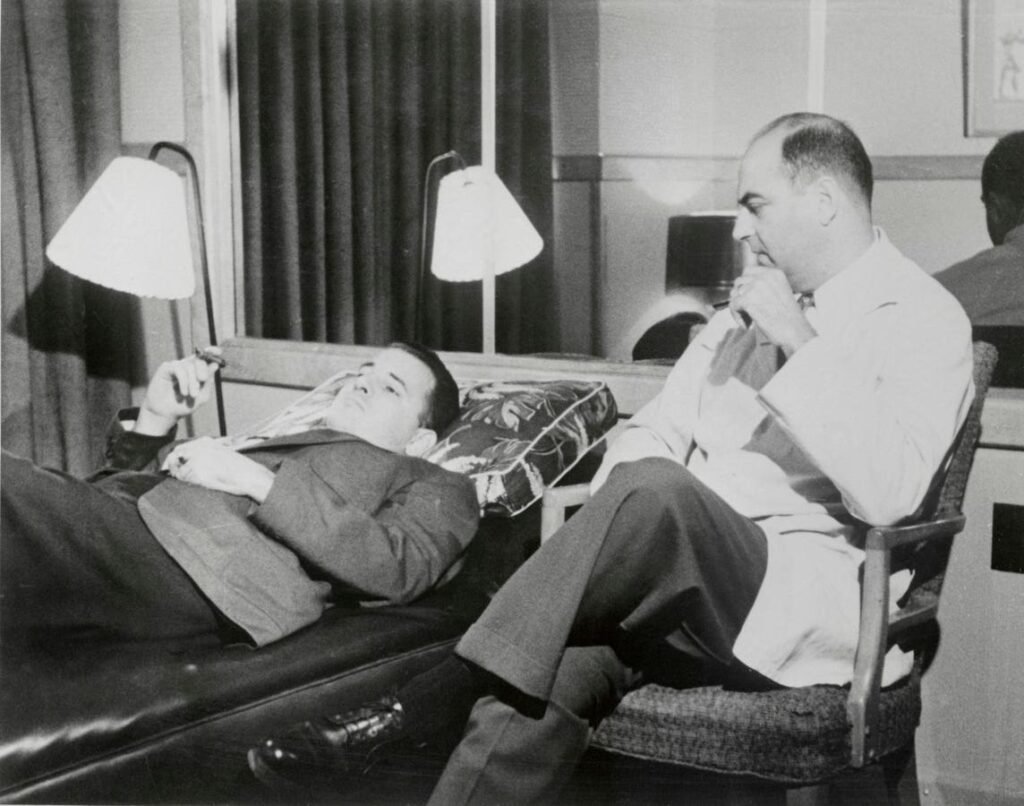

Dr. Lief, of the psychiatric department of the Tulane University School of Medicine, conducting a … More

In the late 1970s, when I started in the workforce field, persons with serious mental illness (SMI)—severe depression, severe anxiety, bi-polar disorder, schizophrenia spectrum disorder—were not even on America’s workforce agenda. If they were recognized at all, they were seen as in need of recovery, too damaged, unable to function in the mainstream economy.

This would change in the next two decades, as understanding of mental illness increased and employment came to be identified as central to recovery and individual health. The development of the Individualized Placement and Support model in the 1990s for persons with SMI moved forward the process of employment in mainstream workplaces, setting out a form and protocols for individual placements.

Today a new stage of workforce activity is emerging, seeking to go beyond individual placements. Major employers are being enlisted. The goal: develop new workplace structures to increase the hiring of individuals with SMI and increase their retention.

One of the centers of these efforts is One Mind, the mental health non-profit and volunteer group, based in Napa, California. One Mind sponsors projects of applied research, teaching, mental health start-ups, and employment. Currently, One Mind is getting ready to pilot its largest employment project, One Mind Launchpad.

Serious Mental Illness and Employment: The Prevailing Model of Job Placement and Supports

The prevailing model of employment for persons with SMI is a high touch, high support model, influenced by the work of Dr. Robert Drake. Soon after Dr. Drake began his practice in the mental health field in the late 1980s, he was told by a director of mental health in New Hampshire: “What clients say every year is that their first goal is to get a job, but we don’t know how to help them.”

Drake experimented with several approaches before settling in the early 1990s on an approach he called Individual Placement and Support (IPS). IPS emphasized rapid placement in a job with mental health supports. Drake came to believe in most cases, clients with severe mental health challenges did not benefit from the extensive pre-employment training, counseling and evaluation. Rather, they responded better, were better able to help manage their mental health condition, if they were placed rapidly in a job, where they had a sense of purpose and structure, a role in the community, and interaction with others.

Drake and a colleague launched an IPS pilot in New Hampshire in the early 1990s, and then followed with pilots in a mix of rural and urban areas, including in inner city Washington DC. In these pilots, Drake utilized randomized controlled trials, comparing the employment and mental health outcomes for participants against outcomes for individuals with similar mental health conditions. He publicized the results throughout the mental health communities. He described the jobs approach as a more effective intervention than the therapies and medications that often were relied on. He contrasted the job approach with the government benefit and healthcare systems which conveyed a message to individuals with mental health conditions that they were “broken, not competent, cannot succeed in life”.

“Previously we told people to stay in the hospital for six months or stay at home for two years to recover, but that has all kinds of harmful effects. If we can get people out working, it builds resilience that will benefit them throughout their lives.”

Since the 1990s, the IPS model has been taken up widely. Today IPS programs are operating in forty states and 20 countries in North America, Europe, Asia and Australia. A library of IPS manuals and sets of protocols has been developed for job placement of mental health clients, An IPS Employment Center for research and technical assistance has been established at Colombia University.

Despite its success, IPS has been limited in reach by its high cost per participant, compared to other targeted employment programs, as well as by the challenge of engaging employers. Workforce practitioners and behavioral health specialists have been searching for ways to expand the number of employment placements and at the same time impact workplace culture.

Building on the IPS Model: Engaging Employers, Scaling Employment Services

Brandon Staglin

One Mind Launchpad is headed by Brandon Staglin, himself a person living with schizophrenia spectrum disorder. This brain disorder–characterized by delusions, hallucinations and disorganized thinking—affects an estimated 2.8-3.2 million Americans

Staglin was a freshman at Dartmouth in 1990, when he had his first psychotic episode. He took time to recover, and was able to return within six months and graduate with a degree in Engineering Sciences in 1994. He returned to California and was hired as an engineer with Space Systems/Loral, as part of a team designing spacecraft for commercial and government uses.

After a few years he was accepted to the graduate program in engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. But before he could enroll, he suffered another psychotic episode that left him disoriented and unable to function. He would recover, through a program of cognitive training, and return to a job. In the meantime, his mother, Shari Staglin, and father, venture capitalist Garen Staglin, decided to address SMI on a broader basis. Garen recalls “Brandon told me that we could either run away from severe mental illness or run toward it.”

Over the past nearly three decades, One Mind has established a series of projects: One Mind Accelerator, to promote startups aimed at mental health treatments and diagnostics, One Mind Academy, funding translational research in brain science and mental health, One Mind Lived Experience giving voice in program and policy development to persons with the lived experience of SMI, and One Mind at Work, the initiative to empower organizational leaders to promote and provide for the mental health of their workforces.

One Mind at Work, established in 2017, started by identifying best practices for supporting workforce wellbeing and performance, and developing its Mental Health at Work Index, challenging companies to test and evaluate their practices. It assembled an employer advisory council, from its membership of over 130 major companies–dues-paying members who committed to mental health inclusion. One Mind was able to draw on Garen Staglin’s contact list of CEOs, and on the emergence of mental health as a workplace issue. As Garen notes, “In reaching out, I soon found nearly all executives had some person close to them with SMI issues—a family member, friend, neighbor, and the issue of severe mental health and employment resonated with them.” Accenture, Bank of America, Capital Group and Mars, are some of the companies most actively involved.

The Interplay of Serious Mental Illness and Workplace Culture

The new project One Mind Launchpad will guide employers to provide support more directly to young workers with significant mental conditions, and seek to scale placement efforts. It is set to start a pilot phase in January 2026, and Brandon Staglin is currently interviewing companies from the employer advisory council to be among the pilot companies.

The pilot will start with 3 companies. Each company will partner with One Mind to tailor a mental health strategy to its needs. All of the strategies, though, will combine elements that One Mind has come to see as needed for effective hiring, retention, and career growth :

Participation at all levels of the company’s workforce: A multi-year commitment by the company CEO and other C-suite executives, along with the training of supervisors, managers and co-workers.

Involvement of One Mind’s Lived Experience group: Training of executives and others by members of One Mind’s group of persons with SMI who can detail their own experiences in the workplace, and lessons from these experiences.

Supports individualized to each worker: “If you’ve met one person with SMI, you’ve met one person with SMI”, One Mind says in relation to the supports individualized to each worker (a similar saying is part of the neurodiversity community).

Measurement of outcomes, open reporting, and tracking of participants for a period of years: Perhaps most importantly, a foundational principle of One Mind is that outcomes be measured and reported openly. Employment of participants will be tracked for at least a five year period.

In January 2027, the project will enroll its first participants: 50 young persons with significant mental health conditions to be hired into companies, 50 incumbent workers with such conditions to successfully retain their jobs, and 25 incumbent workers promoted to higher level roles. Beginning in 2028, the project is expected to grow rapidly. The goal is for a total of 14,700 persons with SMI served through the first five years of the project, with further major expansion planned in the following 5 years.

Serious Mental Illness: The Power of the Job

With One Mind Launchpad, One Mind joins several other major mental health organizations, including the prominent Fountain House entities, that are seeking today to both scale and to impact workplace culture. It joins complementary workplace culture and supports initiatives by organizations engaged in expanding employment for adults with autism and other neurodiverse conditions.

Dr. Kathy Pike, the CEO of One Mind since 2023, has seen the power of the job, over her more than thirty years of research and practice with persons with SMI. Having a job, the structure and economic role, enables persons with SMI “to manage their conditions, to live fulfilling lives, to be part of society as we all seek to be.”

Dr. Pike notes that any employment effort needs to build on the lessons of the recent decades, and be thoughtfully implemented. Care needs to be taken to get a good job fit, one in which the worker is able to truly contribute to the company. The responsibilities of the company, managers and co-workers need to be recognized at each stage of program implementation. The employment team will draw on support networks outside the workplace—family members, friends, mental health professionals.

Through the structure of the job, a person with SMI is often able to better address other conflicts in their lives that previously seemed overwhelming. Significant mental health conditions may not be “cured”, but they can be effectively managed.

The Neurologist’s Brother

In his autobiography, On the Move, Oliver Sacks, one of the most influential neurologists of the past half century, discusses his brother Michael, who battled schizophrenia throughout his life. At an early age, Michael showed signs of high intellectual promise (in his youth Michael was able to recite Nicolas Nickleby and David Copperfield by memory), but at age fifteen began to show signs of schizophrenia and at age sixteen was admitted to a psychiatric hospital. Through a family friend, Michael at seventeen was able to find employment as a delivery messenger, and it became a job he worked at for 35 years until his company went out of business. During the time he was employed, he was able to manage his schizophrenia. But after losing his job his isolation increased and his health declined, and he passed away a few years after. Sacks laments that he was not able to assist his brother with finding new employment, and what loss of employment meant for his brother.

Finding, maintaining, and developing employment for persons with SMI often will be a challenging process—one that even Oliver Sacks could not successfully achieve for his brother. The extent to which One Mind Launchpad will succeed in the next five years remains to be determined. But its heightened engagement of employers (“all in”), supports within the workplace, and supports outside of the workplace, will command attention among workforce practitioners and scholars.