Time—or the lack of it—could be a missing link in dementia prevention, according to a recent paper from UNSW Sydney’s Center for Healthy Brain Aging (CHeBA). Published in The Lancet Healthy Longevity, the article highlights time as an under-recognized social determinant of brain health, potentially as crucial as factors like education and income. The concept of “temporal inequity” is introduced, referring to the unequal distribution of time across different societal groups, which may hinder individuals’ ability to reduce their risk of dementia.

Lead author Associate Professor Susanne Röhr, an expert in social determinants of health, emphasizes that lifestyle factors such as sleep, physical activity, nutrition, and social engagement are essential for brain health, yet all require a critical resource: time. Up to 45% of dementia cases globally could be prevented by addressing modifiable risk factors, but many individuals lack the discretionary time needed to engage in brain-healthy activities. This “time poverty” acts as a hidden barrier to reducing dementia risk.

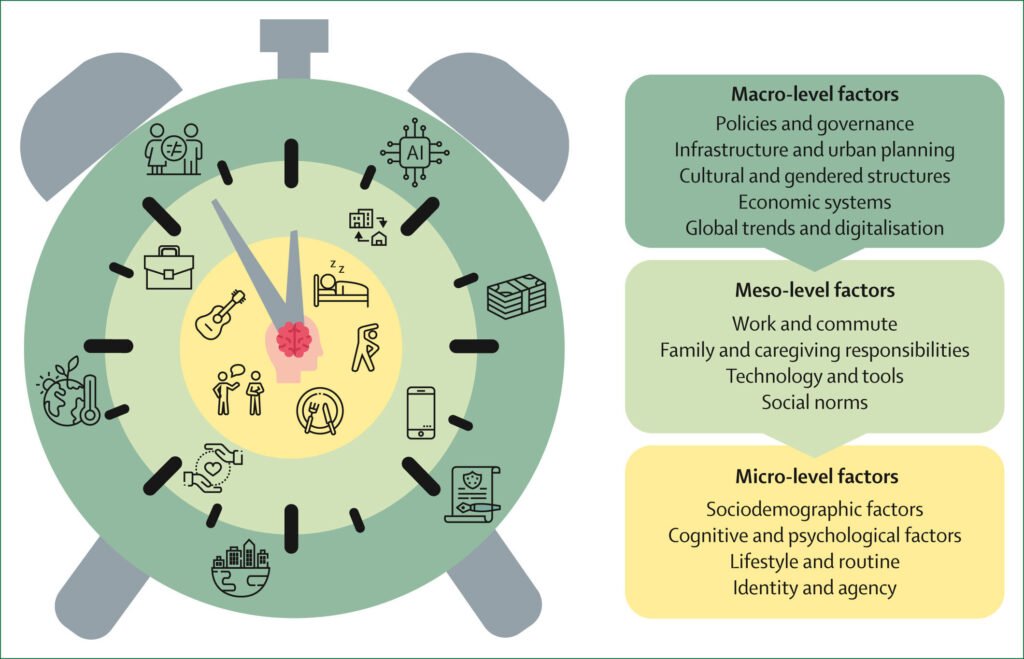

The research sheds light on how structural conditions like long working hours, caregiving responsibilities, digital overload, and socioeconomic disadvantage contribute to “time poverty,” disproportionately affecting vulnerable groups and exacerbating existing health disparities. CHeBA Co-Director Professor Perminder Sachdev emphasizes the need for a shift in dementia prevention strategies to address time as a social determinant of health.

The authors advocate for policy and workplace reforms focused on “temporal justice,” which aim to protect and redistribute time to ensure everyone has access to brain-healthy opportunities. Examples include flexible working arrangements, rights to disconnect, affordable childcare, and investments in public transport to reduce commuting times. Associate Professor Simone Reppermund stresses the importance of future research capturing the realistic time needed for brain care, suggesting that at least 10 hours per day are necessary for essential brain health activities.

Recognizing time as both a resource and a source of inequity, the researchers urge governments, researchers, and communities to integrate temporal justice into dementia prevention strategies. By addressing time poverty, they believe it is possible to make significant strides in preventing dementia and promoting overall brain health. The study’s findings underline the critical role that time plays in shaping health outcomes and emphasize the need for a more holistic approach to healthcare that considers temporal equity alongside other social determinants.